HISTORY

A BRIEF OVERVIEW

by Chris Sullivan MA FSA

Apart from a little Bronze Age pottery nearby, archaeology at Lydney Park starts with the spectacularly-sited Iron Age hill fort above the Spring Garden. The Romans converted this to a healing temple site, with a large guest-house for pilgrims and a luxurious Bath-house, with wall plaster and mosaics. This important site was first excavated by Charles Bathurst from 1805. He secured finds including the first Curse Tablet found in England, beloved of Tolkien fans; a new god Nodens; beautiful mosaics, re-covered for safe-keeping; and the Lydney Dog we use in our branding.

New invaders, the Normans, took over Domesday’s ‘Lindenee’. To the west of the current house are vestiges of a 12th century castle. Lydney passed through two great families, the Talbots and the Warwicks, until one of Elizabeth’s Admirals, Sir William Winter, built up a Lydney Park landholding. His descendants, particularly Sir John, Secretary to King Charles 1st’s Queen, invested heavily in iron production. Sir John lost almost everything in the Civil War, and 300 years ago Lydney Park passed to a branch of the Bathursts, here still today. Successive Bathursts have been involved in ‘County Business’, or national affairs, as well as the development of local industry. The fourth Charles Bathurst was ennobled for services to food supplies in the First World War. Devoting his considerable energies to the improvement of farming here and abroad, he became a Viscount after service as New Zealand’s Governor-General.

Outbuildings of the Wintour-era house are in use at Taurus Crafts, and old maps show the ‘Pleasure Gardens’ around it. A new house was built from 1875. Its gardens were converted to food production in the Second World War, when the house sheltered first the future Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, then the North Foreland Lodge girls’ school. Benjamin, the second Viscount, largely created the beloved Spring Garden. Grandson Rupert is now developing this mature planting to diversify and prolong its season of beauty.

A Fuller History

by Chris Sullivan MA fsa

PRE-ROMAN

The Neolithic and Bronze Age have so far yielded very sparse findings across the Forest of Dean. In the early Iron Age, perhaps 2900 years ago, Lydney Park’s hill fort was created. It is of the ‘promontory’ type, on the ridge above the Spring Garden and with a huge panorama including other hill fort sites. Its Iron Age pottery is of the same Silurian style as in hill forts just into modern Wales.

ROMAN

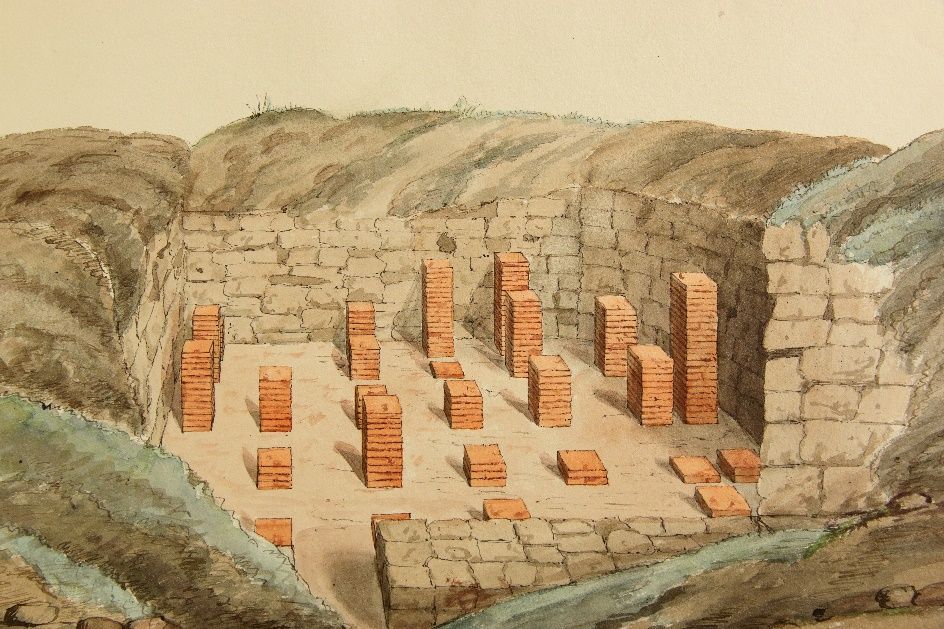

Perhaps the Roman army rolled through Lydney around AD 49 on its way to subdue the Silures. In the second half of the 3rd century, a Roman temple of unusual design was created, probably enhancing an existing but undetected Celtic ritual site in the hill fort. The temple complex grew into a healing site, with a large villa or guest-house for patients or pilgrims and a luxurious Bath-house, with beautiful mosaics and wall plaster. The complex perhaps went into serious decline in the second part of the fourth century AD.

From 1805 the site was first secured from casual looting, then systematically excavated and recorded, by the first of the Charles Bathursts who have lived at Lydney Park. Bathurst died before publishing, but his work in mapping the site and recording its artefacts and mosaics is the foundation of studies today of this much-discussed site. We have put a copy of his notebooks into Gloucestershire Archives for the benefit of scholars, in the huge D421 range of archives from the 13th century which the family has put there.

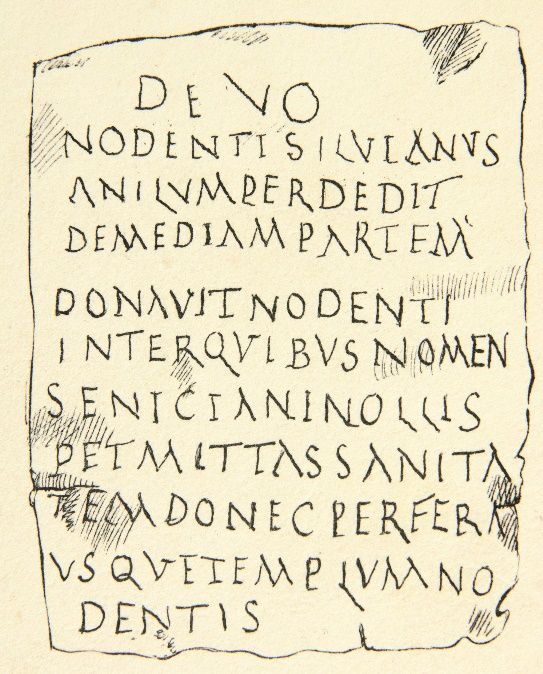

Bathurst found three ‘votive’ items from the temple area. All invoke a previously-unknown god, Nodens. One was the first ‘curse tablet’ found in the UK, asking Nodens to deny health to Senicianus who has stolen a ring. Some argue that this is the same ring as Bathurst knew had been found, reinscribed ‘Senicianus’, in Silchester. And some argue that the stolen ring seeded JRR Tolkien’s ideas when he contributed to the excavation report done by the Wheelers under Lord Bledisloe, the fourth Charles Bathurst.

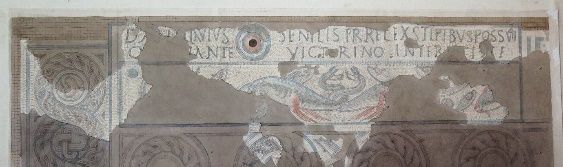

The first Bathurst viewed the number of dog images, including the beautiful little “Lydney Dog” in bronze, as indicating a link with the dog-protected Greek god of healing, Aesculapius. He had discovered a “collyrium stamp”, for labelling three types of Roman eye medicine. He coupled these to conclude that Lydney Park was a healing site under Nodens. Other finds suggested a hunting nature for Nodens and a link to the Severn Estuary, even to the Severn Bore. Even in Bathurst’s time, many of the fine mosaics had been severely damaged by stone-robbers or iron-miners. After the Wheeler re-excavation in 1928-9, and a limited one in 1999, the mosaics and the guest-house site have been covered up for safe-keeping. So his drawings are the best current guide to what was there. Some have been published in articles on this excavation in The Forest of Dean Local History Society’s New Regard no 36

...and a more scholarly version:

"BATHURST'S UNCOVERING:

Charles Bragge Bathurst, First Excavator of the Lydney Park Roman Temple"

By Chris Sullivan MA

Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Vol 139, 2021. That Society has kindly allowed us to use their copyright material which can be viewed here

Post-Roman to Early Modern

Grants of Lydney land are known in Saxon times, with Lideneg recorded around 853. William FitzOsbern, William the Conqueror’s right-hand man, created a Lydney manor out of church lands and the property of two thanes. Excavations done, at Little Camp Hill opposite the Roman site, produced remains including a Norman stone keep dating to the 12th century.

‘FitzOsbern erected a small castle, now under the Shell Keep at Berkeley Castle, to guard a Severn crossing to his lands in the Welsh Marches. The outline of a matching castle at Lydney Park may just be discerned underneath a replacement structure, perhaps of the time of Henry 1st. There is essentially nothing to see of this today, beyond some earthworks full of stone fragments. The small site, by the main House, is not open.

Charles Bathurst was aware of past Roman finds on the site, but it was not until 1931 that a dig report was published. That showed little more than a fortified look-out, with a sturdy keep, curtain walls with a gate-house, and some earthwork defences. Much of the buried stone looked like it had come from the temple across the valley, and the oven floor was paved with hypocaust tiles from the Bath-house. Some of the few pottery finds dated to the late Saxon, and there was a broken Viking-style padlock. Evidence that Lydney Park remained important between the Romans and mediaeval times.

Until Tudor times, land around Lydney passed down two great families, the Warwicks and the Talbots of Shrewsbury. So it was termed Lydney Warwick or Lydney Shrewsbury. In the mid 1500’s both sets of lands, plus lands from Queen Elizabeth, were sold to Admiral Sir John Winter, active even in his 60s against the Armada. His son Edward was captured by the Spanish, raised his own ransom, and retreated to Lydney to produce iron, essential for making military goods and otherwise imported. Edward’s son Sir John became one of the country’s largest ironmasters, turning decrepit forest into organised coppice on a large scale. This and his Catholicism made him unpopular locally. Loyal to King Charles, and Secretary to his French Queen, he lost almost everything in the Civil War. That included his manor house, burnt to deny it to the Roundheads. His son Charles built a new house, but Charles’ widow Frances was reduced to selling up ‘a great house, with large beautiful gardens, and a large park’.

300 years of Bathursts

The purchaser was Benjamin Bathurst (1688-1767). The sale was made on securities in 1723, with funds raised through an Act of Parliament in 1724.

Benjamin’s father was Sir Benjamin Bathurst (c 1635-1704). Sir Benjamin’s grandfather was a London alderman for the Grocers’ Livery Company, importing exotic items. Six of Sir Benjamin’s brothers were killed fighting for King Charles in the Civil War, and understandably Benjamin sat out the Interregnum abroad. Perhaps drawing on his grandfather’s connections, he was recorded as a merchant at Seville in 1672/3. He bought lands in Paulerspury, Northamptonshire in 1673-4 as “a London merchant then living at Seville”. When he died, some of his property was abroad. Indeed, he left a bequest to someone who had become a nun in Seville!

Back in London, Sir Benjamin became a stalwart in all of the East India Company, the Levant Company and the Royal African Company (RAC). These companies held the monopoly of all English trade whether east or west of Africa and in the Middle East, all highly relevant to a merchant. Most regrettably, the Royal African Company, making little money by two-way trade at a time of war with the French, got involved with the export of English textiles to fund purchases of convicts and prisoners of war from the African slave markets, and their transportation west. The RAC, like its predecessor, went bankrupt. Its dividend stream and boardroom pay could have added little to Sir Benjamin’s substantial wealth. But from 1677 to 1695 he was at or near the top of this slaving organisation, sometimes only below Duke (later King) James. It is a matter of great sadness that our distant forebear had this involvement, which is why we place the matter on our public record.

At the time, this involvement would have been no stain on Sir Benjamin’s character. He was knighted for public service like other Directors of the RAC. He married Frances Apsley, a close confidant of both James’s daughters, Mary (as in ‘William and Mary’ of the Glorious Revolution) and Anne (later Queen Anne). He became financial manager for James Duke of York, for Princess and Queen Anne, for Anne’s husband George and for their intended heir, William.

Sir Benjamin died in 1704 leaving daughter Anne and three sons, Allen (who took the main Cirencester and Northamptonshire lands), Peter and Benjamin (who were left lands in Wiltshire, Oxfordshire and elsewhere).

Son Benjamin Bathurst (1688-1767) was brought up at Court, but lived a much less eventful life than his father. We should record him as a junior office-holder in the RAC for a year, but his main tasks seem to be intellectual pursuits and the generation of 36 children from his two wives, Finetta then Catherine. He sold his inherited lands in Oxfordshire to fund the purchase of Lydney Park, “much more Convenient and Advantageous for the said Family.” Arriving at Lydney, he set a labourer to clear the ‘Wilderness’ at ‘Dwarf’s Hill’- the Roman temple site. This exposed the Roman site to casual removal of coins and other items, with locals taking the stone walls.

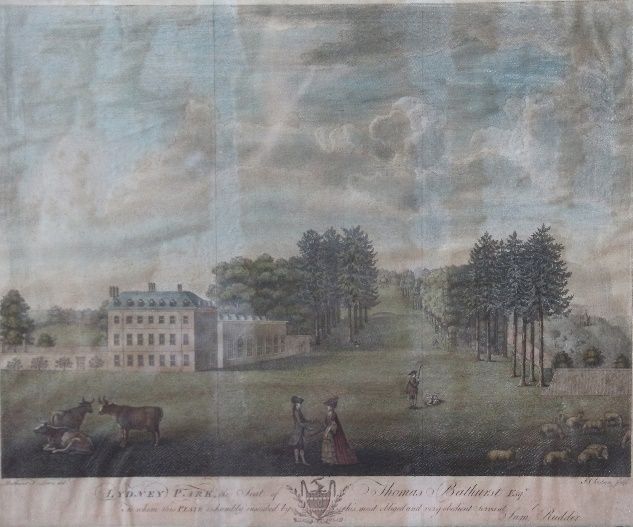

His eldest son, Thomas Bathurst (1725- c1792), married Ann Fazakerley, with mining lands north of Liverpool. By the early 1770s the Park had a number of ornamental features, and a terrace and Gothic summer house had been built on Red Hill on the north-east side of it. Maps still show “The Old Pleasure Gardens”. At the entrance to the modern Spring Garden, there are two Roman, or Roman-style, statues. Thomas retrieved these from being used to press flax and set them up at Dwarf’s Hill.

The estate passed on Thomas’s death through brother Poole and his wife Anne, to nephew Charles Bragge (1754-1831) of Mangotsfield near Bristol. Bragge changed his name to Charles Bathurst on inheriting, in 1804, an estate sufficiently modest that he needed to find jobs, including in politics. At school, Bragge Bathurst made a friend key to his future direction – future Prime Minister Henry Addington. He later married Addington’s sister Charlotte. Charles Bathurst followed grandfather Benjamin Bathurst’s footsteps to become MP for Monmouth in 1790. He represented Bristol from 1796 until 1812. Perhaps a dutiful constituency MP for Bristol could not be on the side of the angels in the 1807 debates on the Slave Trade Abolition Bill. On 23 February, backed by his brother-in-law Hiley Addington, he merely recommended a tax on the importation of fresh slaves, as a measure which would ultimately lead to total abolition. The mood of Parliament, and the tide of history, was against him.

Charles Bathurst represented Bodmin (1812 -1818) and Harwich (1818-1823), seats cheaper at election time than Bristol. Bathurst was a regular speaker in the Commons on a wide range of Governmental and Commons Committee matters. He does not seem to have been a gripping orator. He was more a conservative in legal and procedural matters, a thinker rather than a charismatic leader. At the start of the Napoleonic Wars, he was Navy Treasurer, then was Secretary at War. Later he was Master of the Mint, and had a Cabinet-level post as Chancellor of the Duchy. For many years he ran Gloucestershire ‘County Business’ as Chair of the Quarter Sessions. In Lydney, he was active in the proposals for the Lydney Docks canal and tramroad. Early in his tenure at Lydney Park, he planted a range of foreign trees. His handwritten tree lists survive. His pioneering archaeology has been covered in the ‘Roman’ section above. He died in 1831.

He was succeeded by a second Charles Bathurst (1790-1863). Often incapacitated by illness, he nevertheless was instrumental in making Gloucestershire the first county to appoint a Chief Constable. He was one of the Dean Forest Commissioners who between 1831 and 1835 settled today’s boundaries of the ‘Statutory Forest’; allowed long-standing squatters to buy their freehold; and provided two Parishes to the extra-parochial Forest.

He died childless in 1863, the estate passing to his brother Revd William Hiley Bathurst (1796-1877), a retired Rector and hymn-writer then aged 67. The family involvement in coal, ironworking, railways and now tinplate continued under William. He followed his brother in supporting religious and educational institutions. All Saints Church, Viney Hill was built as a memorial to Charles, with widow Mary. William paid much of the capital and running costs of Aylburton Church of England School, and gave the land for the Lydney one.

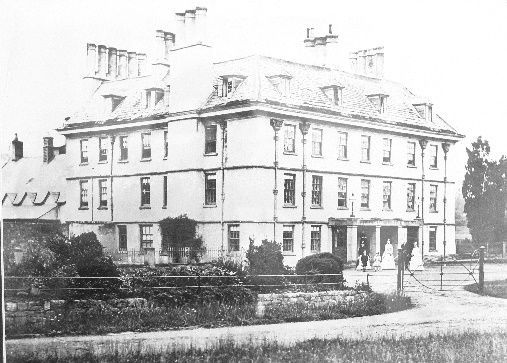

In 1875, he decided to move the family home uphill, away from the damp Wintour-

era site. C.H. Howell designed the present Tudor-style mansion in rusticated

stonework with a castellated tower at one corner. The old house, apart from part of the stable block and the laundry, still in the Taurus Crafts area, was then demolished.

Marrying Mary Rhodes in 1829, William had a son, yet another Charles, and three

daughters. He died on 25 November 1887.

William’s son Charles Bathurst (1835-1907) followed the mainstream Lydney Bathurst course of becoming a barrister after an Oxford degree. Like his father, he was a magistrate rather than an MP. In 1892, he gave Bathurst Park to Lydney, to mark his eldest son Charles’s coming of age (then at 25). In 1896, he was one of the Trustees of the new Lydney Institute. Lydney was suffering serious housing shortages, so parcels of Lydney Park land were sold for workers’ homes until the First World War. Charles married Mary Hay in 1864. In 1882 she opened the subscription funded Aylburton cottage hospital “mainly established through the instrumentality of Mrs Bathurst”. Charles died in 1907. He had two daughters and four sons. William Hay Bathurst died of meningitis, aged only 18, in 1883.

On Charles’s death in 1907, Lydney Park passed to his second son, our fourth Charles Bathurst (1867-1958). Charles Bathurst was trained both as a lawyer and an agriculturalist. Most of his life was devoted to improving agriculture here and abroad. He married Bertha Lopes in 1898. Their children were Benjamin, Hiley and Ursula. In the first week of Lloyd George’s Prime Ministership, reservist Captain Bathurst MP was called to attend a War Cabinet discussion of agriculture. He left as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Food Control. Meanwhile wife Bertha was running the Red Cross Hospital at Lydney Town Hall. His wartime work led to a knighthood, then a peerage as Lord Bledisloe, from the name of an old local Hundred. Post-war, that peerage denied him the job he wanted, Agriculture Minister, but he remained a loyal junior Minister until Bertha’s death in 1926. At the age of 60, in 1928 he married the Hon. Alina (‘Elaine’) Cooper-Smith, a daughter of a Welsh tin-plate manufacturer.

Locally, he donated Bathurst Pool to Lydney in 1920 on the coming of age of son Benjamin. Interested in the co-operative movement, in 1923 his farming experiments included local factories and profit-sharing for employees. The Lydney hospital moved to its current position, built on Bathurst land in 1908. It was enlarged between 1935 and 1937 by the addition of a maternity wing and out-patient department, given by Viscount Bledisloe as a memorial to his first wife. A new physiotherapy centre was completed in 1963 as a memorial to Viscount Bledisloe. He was a magistrate, a Verderer for 55 years and a President of many Lydney societies. He was Governor-General of New Zealand between 1930 and 1935 and was highly popular and respected, including by Maori leaders. He purchased for the New Zealand nation the site of the Waitangi Treaty, as part of his aim of giving greater respect to the Maori Kings and Maori history. Antipodean Rugby fans will know of the Bledisloe Cup. In wartime, he offered his house first to Princess (later Queen) Marina of the Netherlands and her children, then to the North Foreland Lodge girls’ school. Elaine died in 1956, Charles in 1958.

Charles was succeeded by Benjamin, 2nd Viscount Bledisloe, (1899-1979). Benjamin was an accomplished rower, skier and alpine mountaineer, and a cup-winner on the Cresta Run. He was an air transport Commander in the Second World War. He was also a trustee of the actors’ Garrick Club. In 1933, he married Joan Krishaber, who died in 1999. The rest of her family had perished in the Holocaust. Their children were Christopher and David. From 1950, he set about reversing wartime conversion of the gardens to food production. In 1962, he added new fountains at the front of the house. The mid-60s saw major hands-on landscaping and the creation of new dams and hence lakes, clearance of a large area of woodland, and replacement by a wide range of Rhododendron cultivars and species, plus other trees and shrubs. The round ‘Temple’ was brought over from Venice. Benjamin was a Queen’s Counsel, and his many contributions in the House of Lords reflected analytical as well as civil liberties thinking.

Christopher, 3rd Viscount Bledisloe (1934- 2009) was another Queen’s Counsel, with a large and distinguished commercial caseload as well as being Head of Fountain Court Chambers. He was one of the Hereditary Peers elected to sit, with a similar style of intervention to his father’s, and a focus on European business. He married Elizabeth Thompson in 1962, with children Rupert, Otto and Matilda. He added new planting to the Rhododendron Garden and was also President of the Cresta Run.

On his death, Rupert, 4th Viscount Bledisloe (1964 -) set a different path through the family’s 300th anniversary at Lydney Park. An artist from childhood, Oppidan Scholar at Eton, with further education in English and Drama and a mature MA in fine Art, he works and exhibits in London. His practice encompasses relatively traditional portraiture, of people as varied as Francis Bacon and Keith Richards, to multi-media, experimental portraiture, abstracted colourfields and three-dimensional work exploring trauma and redemption...

He married Shera Sarosh in 2001. Their children are Iona, Benjamin and Agnes. With Matt's Gallery, London, he has co-generated Art Residencies across various elements of the estate. With eminent garden designer Charles Chesshire, he is restoring neglected landscapes and buildings, seeking to re-invigorate his grandfather’s now-mature garden plantings, and further extend the garden’s range and season of interest, while wrestling with the problems of maintaining a viable estate, offering jobs and public interest, in a post-Covid world.